Jumping into this series for the first time? Nah…you’re really going to want to read Part 1, Part 2, and Part 3 first.

In about 2 weeks, my alma mater, the Moody Bible Institute in Chicago, will have its biggest event of the year: Founder’s Week.1 Founder’s Week is a large-scale conference featuring A-List preachers and evangelical NGO leaders2. Classes are suspended, campus is full of visitors. I really loved it as a student, and, despite my disgruntlement toward evangelicalism at times, I imagine I would still love it.

When I looked at the Founder’s Week line-up of speakers, I would tend to think: this is what achievement/success/reaching full potential looks like. There was some big part of me watching the John Pipers, the Alistair Beggs, the James MacDonalds thinking I want that. If I reach my potential, it should look something like this.

I think most of us would recognize that as deeply toxic thinking. Why did I think that way? Was it mostly my own grandiosity or insecurity or need for attention? Was it something cultural, either at Moody as an institution, evangelicalism as a religious culture, or related to something more sociologically widespread?

The latter, I believe.

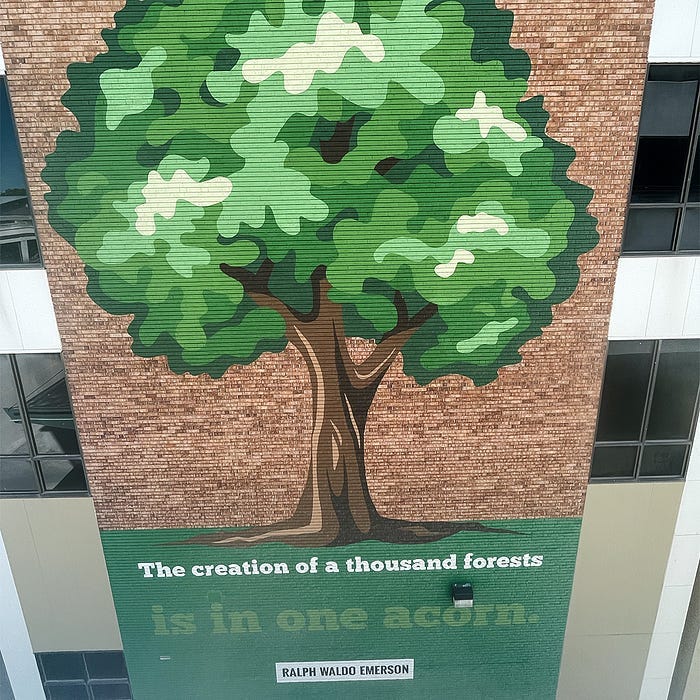

Lincoln, Nebraska is a terrific walking town, and I made full use of it. If you live there and you’ve never walked the MoPac Trail, you’re really not taking full advantage of living there. But when we moved downtown temporarily in 2020, I got to know some parts of the city less familiar to me. Downtown Lincoln is home to some great street murals, and one day I saw this one:

“The creation of a thousand forests is in one acorn.” —Ralph Waldo Emerson

That’s an inspiring thought…from a certain point of view. I mean, good for you, acorns that became a thousand forests. But is that quote also an indictment on the acorn that became a single tree in the park? Or the acorn that got eaten by a squirrel? I mean, they could have become a thousand forests!

What a waste of potential, right?

I had one of the weirdest conversations of my life with my wife Betsy on a snowy January evening. We had just got home from a wonderful event put on by our beloved church, Mosaic Lincoln. It was the first real post-holiday opportunity to just relax with and enjoy our community around tables with good food and beer. As I lapped up authentic community with a side of Scottish ale, I felt something that I found deeply pleasant but vaguely threatening.

I later came to identify it as contentment.

“Sweetie,” I said to Betsy. “I think I’m…happy. Do you think I’m allowed to be happy.”

Because I felt like the farthest thing in the world from a Founders Week Speaker. Like I wasn’t living up to my potential. I was a prison chaplain. A noble profession, to be sure. But, I was also sure that I was supposed to be making a big impact for Christ and His Kingdom. And, much as I felt I was doing something good and, in its way, important, there wasn’t any way I could construe my life as making a big impact for Christ and His Kingdom.

Betsy, of course, was reassuring that yes, of course, I’m allowed to be happy. But I wasn’t about to accept a diagnosis of contentment without a second opinion. So, I had a similar conversation with Curt, my pastor, some time later. I shouldn’t have been surprised, but he knew what I was asking better than I was able to put it into words.

“Oh, yes…I think this is really common among people in ministry. I only discovered a few years ago just how much I had developed an idolatry of impact.”

There are some phrases that you hear in life that hit you like a ton of bricks (and you are required forever after to only write them in italics). For me, idolatry of impact was one of them.

“Having an impact on the world for Jesus and His Kingdom” had become my Hero Project. That’s a phrase that originated in the work of American anthropologist Ernest Becker. I’m going to talk about what he meant by it, but to grossly oversimplify it, a Hero Project is a way that human beings cope with their anxiety, especially death anxiety, by “immortalizing” themselves through heroism.

I, myself, first learned of Becker through the writings of Dr. Richard Beck, an experimental psychologist out of Abilene Christian University. In The Slavery of Death (one of the five books I would take to a desert island), an extended examination of how, in Christian theology, death anxiety is confronted by the work of Jesus on the cross, he writes—

One path is the path of self-esteem, striving to build, perform for, achieve, and secure a sense of significance and self-worth by participating in a "hero project."

The phrase "hero project" comes from the work of Ernest Becker who described how cultures give us a pathway to achieve a "heroic" identity. Cultures help us know if we are winning or losing in the eyes of those around us. How we divide up the successes versus the failures in the world around us--within families, in our workplaces, in the larger American culture--is evidence of the "hero project" at work. You can be either winning or losing in the hero project. But either way, you'll be trapped by neurosis. The winners will be vain, self-absorbed, workaholics, competitive, selfish, egoistic, judgmental, smug, driven, contemptuous, perfectionistic, and haunted by the possibility of loss and failure. If you're losing in the hero project you are insecure, shamed, envious, depressed, and self-loathing. Again, either way, winning or losing, you're doomed to a neurotic existence.

The other path…is to renounce the hero system and receive your identity as a gift.

Well and good, you may think. But what does all of this have to do with the study of human communication? Or religious communication? I want to get to that next, but first I had to tell my own story of discovering how my own anxiety was leading to a Hero Project, leading in turn to an inability to experience contentment (all in a very Christian-flavored way). Having shared that, we can proceed to a discussion of how I work this idea of the Hero Project into my research on religious communication. Stay tuned.

Thinking about which actually has made me realize for the first time that this year would actually be my 20 Year Graduation Anniversary/Reunion, parties for which are often held during Founder’s Week. Shout out and much love to my fellow alumni!

At the time, that meant the likes of John Piper and Andy Stanley. I think most of my fellows would agree, though, that usually the best gems of the week came from the speakers a few steps below in terms of prestige. Bruce Fong (RIP), Larry Crabb (RIP), and Crawford Loritts come immediately to mind. I can remember most of those messages vividly, and, regardless the shifting I may have done between then and now, would still stand firmly behind them. Stanley’s, too. While part of me wonders who gets invited to speak in 2025, I fear to look, lest, I fear, I’ll feel an even deeper estrangement between myself and an institution I love truly, madly, deeply.

Share this post